Divorce Paintings

Jeanette Mundt

Nov6–Dec202025

Company Gallery is pleased to announce Divorce Paintings, Jeanette Mundt’s third solo exhibition with the gallery.

Recently, Mundt’s practice has undergone a decisive evolution, with the physical life of painting now at its center. Confronting what she perceives as a loosening of collective historical memory, Mundt has re-engaged with canonical genres - landscape, still life, the figure and most recently, abstraction - as structural anchors through which to question how contemporary life might still resonate within inherited forms. Though aware of how traditionally minded this may appear, Mundt is driven by a belief that these frameworks remain capable of containing the tensions and ambiguities of the present moment.

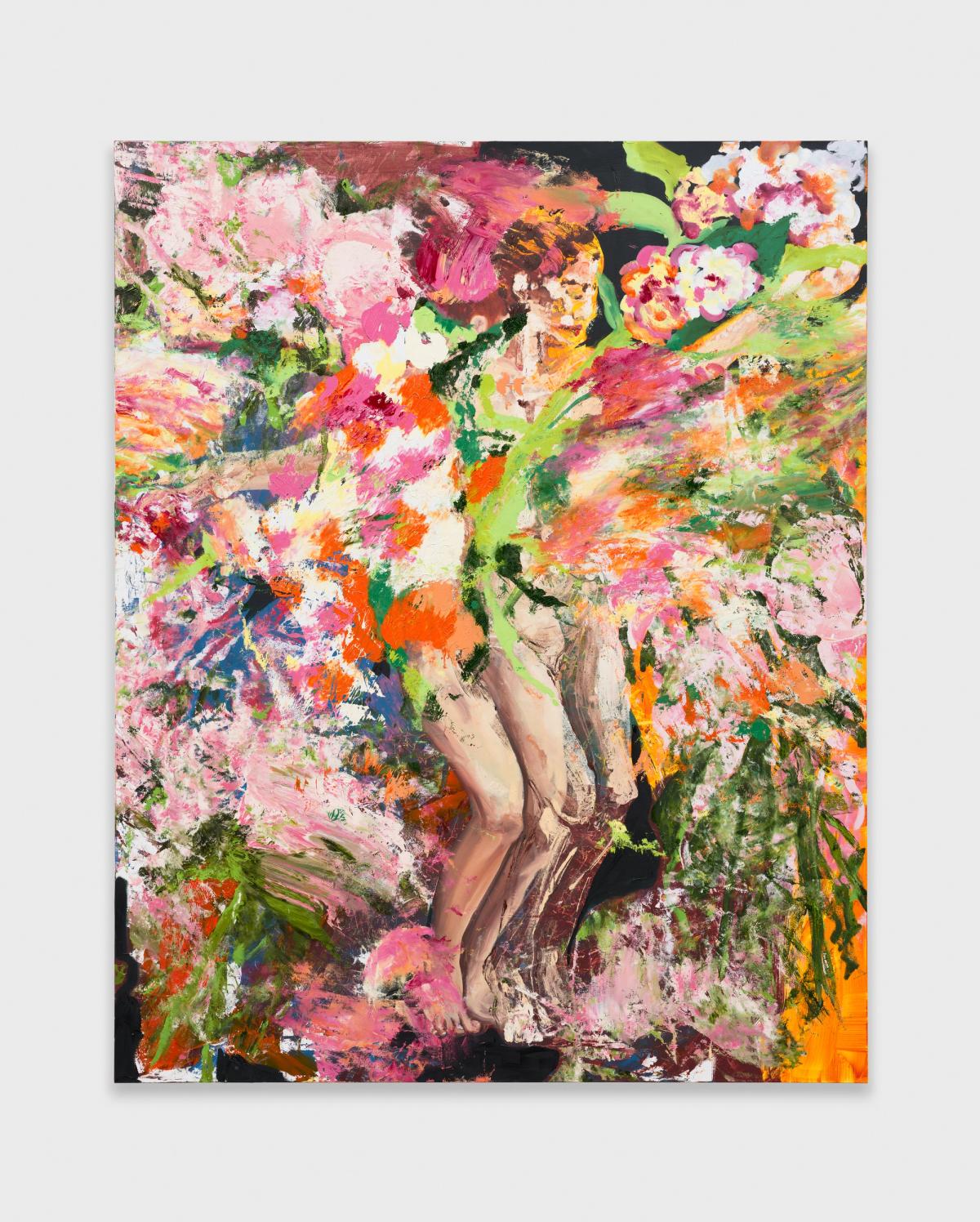

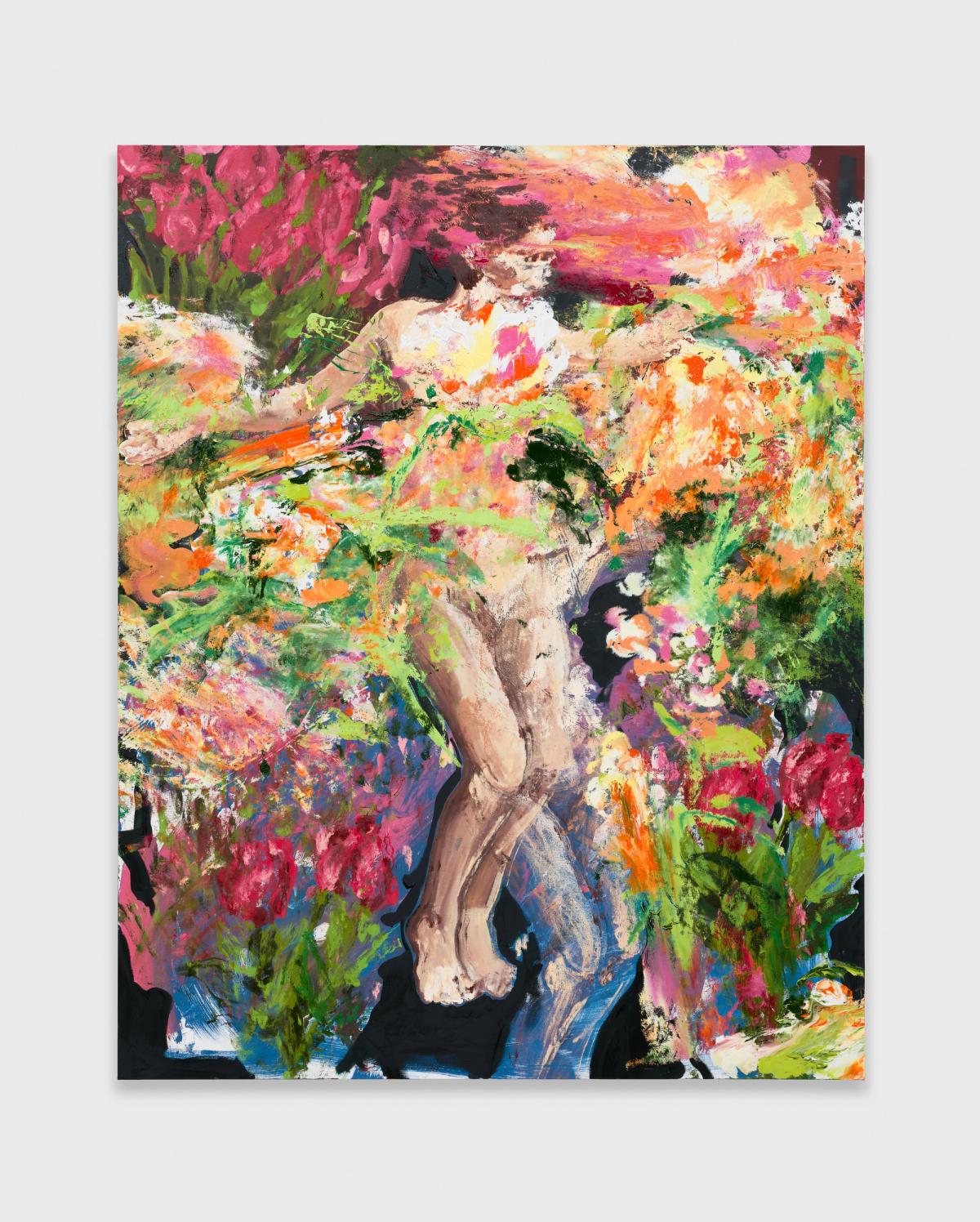

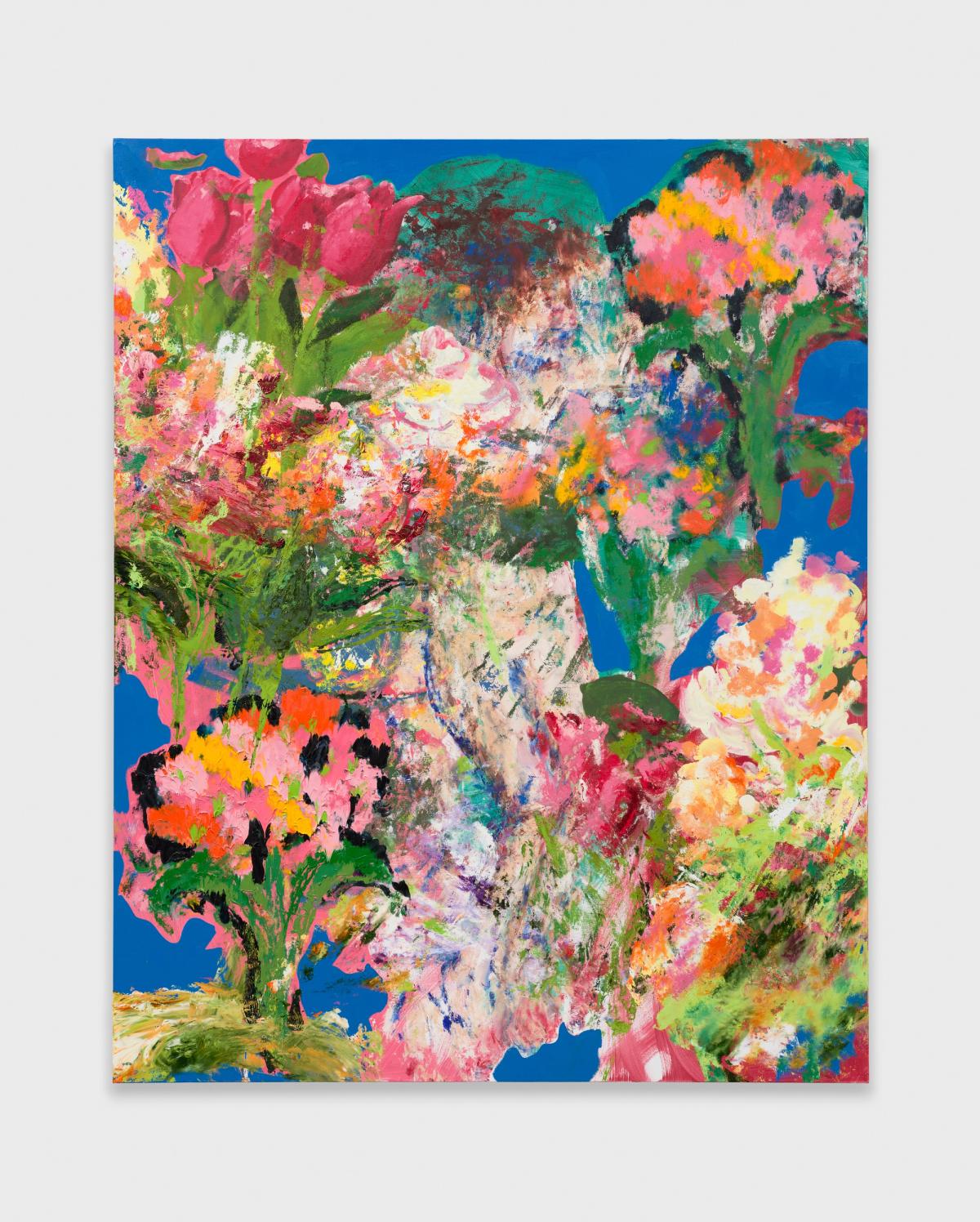

In one series on view, Paul Cézanne’s A Modern Olympia (c. 1873–74) serves as a pivotal point of reference: its mercurial figure recurs throughout, splintered and reassembled through a choreography of transfer, pressure, and erasure. Alongside, a second body of work draws from the promotional poster for the 1999 film American Beauty, with its iconic image of a nude woman nestled in a bed of roses. The composition, with its luminous flesh and floral surround, carries a distinctly Christ-like charge, collapsing sacred and profane registers into a single, seductive image.

Across the exhibition, lush romantic tones press against one another in dense, tactile layers that echo the expressive force of Joan Mitchell and the material experimentation of Sam Gilliam. In particular, Gilliam’s Whirlirama (1970) with its ghostly impressions left by plastic pulled from wet pigment, offered a model for Mundt’s own play between exposure and concealment. Through a similar rhythm of recurrence and transformation, she probes painting’s ability to register movement and duration, turning the surface into a site of charged accumulation where intention and accident converge and each gesture is preserved in the skin of the work.

Mundt’s figures hover at the edge of recognition, continually morphing and collapsing into a looping system where apparitions flicker, multiply, and shift shape from one canvas to the next. Their volatility reflects how the past is increasingly encountered today—not as a cohesive story but as a torrent of unstable images, endlessly revised and recirculated. What once felt fixed now behaves like a feed, capable of rewriting itself with every appearance. Within this atmosphere, the female body becomes both subject and vessel for this instability. She is splintered, reframed, and reinterpreted, her image absorbed into channels where truth and invention constantly intermingle.

Historical narratives follow the same trajectory, mutating with each retelling until their contours begin to blur. Mundt’s paintings neither restore nor clarify these ruptures; instead, they absorb them, allowing distortions to accumulate across their surfaces like sediment. Painting, a medium often dismissed as static, now reveals itself here as uniquely attuned to the chaos of the present. Its slowness counters the velocity of algorithmic distribution. Its physical depth resists the seamless surfaces of screens. Rather than promising certainty, it holds instability in plain view.

Selected Works

Jeanette Mundt

Olympia,

2025

Jeanette Mundt

Olympia,

2025

Jeanette Mundt

Olympia,

2025

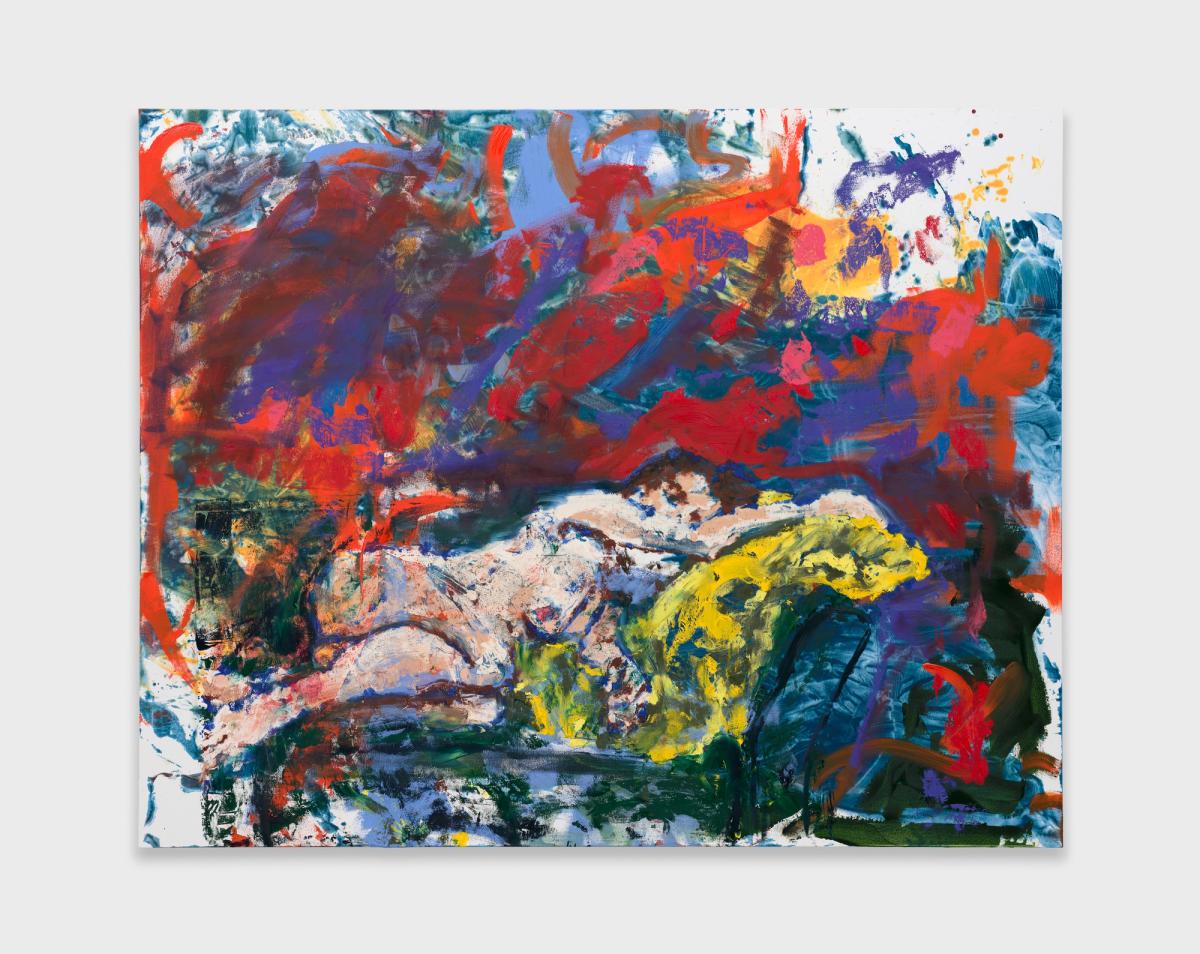

Jeanette Mundt

Broadway Junction,

2024-2025

Jeanette Mundt

American Beauty,

2025

Jeanette Mundt

American Beauty,

2025

Jeanette Mundt

American Beauty,

2025

Jeanette Mundt

American Beauty,

2025